We will be reprinting back issues of the Printed & Bound newsletter on a weekly basis over the next few months.

Printed & Bound focuses on the book as a collectible item and as an example of the printer’s art. It provides information about the history of printing and book production, guidelines for developing a book collection, and news about book-related publications and activities.

Articles published in Printed & Bound may be reprinted free of charge provided that full attribution is given (name and date of publication, title and author of article, and copyright information). Please request permission via email

(pjarvis@nandc.com) before reprinting articles. Unless otherwise noted, all content is written by Paula Jarvis, Editor and Publisher.

Printed & Bound Volume 1 Number 1 October 2014 Issue © 2014 by Paula Jarvis c/o Nolan & Cunnings, Inc. 28800 Mound Road Warren, MI 48092

This issue can be viewed as a PDF here: PandB 2014 Octobermerker5

R.I.P.—KIM MERKER, PRINTER

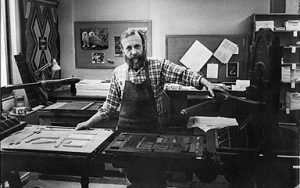

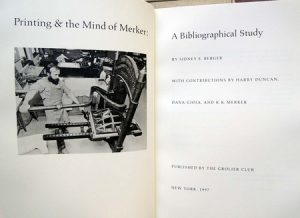

Kim Merker, the man responsible for some of America’s most beautiful books, died on April 28, 2013, at the age of 81. The cause of death was cancer, but his career as a hand-press printer had ended in 1999 when he suffered a stroke.

As founder of Windhover Press at the University of Iowa, Merker did triple duty as designer, typesetter, and printer. In addition, he taught printing crafts, bringing his own experience, expertise, and impeccable taste out of the print shop and into the classroom. Merker told his students that producing a book in the traditional way involved a million different choices, including composition and thickness of paper, typeface, ink color, page size, lines per page, margin size, and countless other small but important details. It was Merker’s attention to such details that made him a leader in the world a fine press publishing.

Born in New York City in 1932, Karl Kimber Merker graduated from Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois. He later lived in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village (where he recited poetry in nightclubs) before joining the writing program at the University of Iowa. There he learned the craft of printing from Harry Duncan, who, in 1982, was described by Newsweek as “the father of the post-World War II private-press movement.”

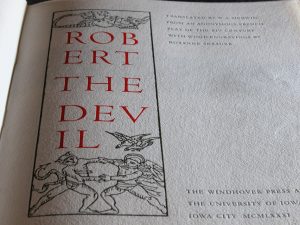

In 1957, Merker founded Stone Wall Press. Ten years later, he established Windhover Press at the University of Iowa. It became the university’s official press and a working laboratory for teaching fine book production. In 1986, Merker created the university’s Center for the Book, an interdisciplinary program for the study of design, papermaking, typography, book preservation, and the history of books.

Young poets, including three future Pulitzer Prize winners (Philip Levine, Mark Strand, and James Tate), were published by Windhover Press while they were still in the early stages of their careers. Under Merker, the press also published works by established writers, including some of Ezra Pound’s last poems and Mary McCarthy’s translation of poetry by Simone Weil. Following Merker’s death, Eric Holzenberg, director of the renowned Grolier Club (perhaps the oldest bibliophilic society in North America), said, “He was the best of his time.” Rest in peace, Kim Merker.—PJ

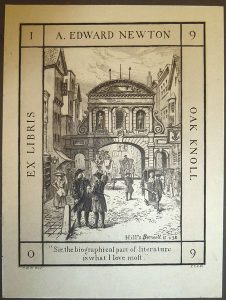

A. EDWARD NEWTON: THE BOOK COLLECTOR’S BOOK COLLECTOR

by Paula Jarvis

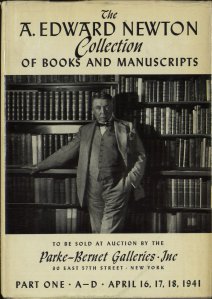

Perhaps the most famous American book collector of the first half of the 20th century, Alfred Edward Newton (1863 or 1864-1940) holds a special place in the annals of American bibliomania. A Philadelphia businessman who became a book collector, author, and publisher, he is perhaps best known to current collectors as the author of Amenities of Book Collecting and Kindred Affections. Published in 1918, Amenities was his first book, and it was an immediate hit among bibliophiles, with more than 25,000 copies being sold during his lifetime. It was followed by numerous other works, including A Magnificent Farce and Other Diversions of a Book Collector (1921), Dr. Johnson: A Play (1923), The Greatest Book in the World (1925), This Book Collecting Game (1928), The Format of the English Novel (1928), A Tourist in Spite of Himself (1930), On Books and Business (1930), End Papers (1933), Derby Day and Other Adventures (1934), Bibliography and PseudoBibliography (1936), and Newton on Blackstone (1937), as well as many articles in the Atlantic Monthly and the Saturday Evening Post. At the time of Newton’s death in 1940, his library, whose contents were assembled with the assistance of such top dealers asGeorge D. Smith and A. S. W. Rosenbach, contained approximately 10,000 books and manuscripts, most of which were English and American literary works. Two highlights among its many treasures were autographed manuscripts of Thomas Hardy’s novel Far from the Madding Crowd and Charles Lamb’s essay Dream Children.

Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York auctioned most of Newton’s collection in April, May, and October of 1941. Because rare book prices had fallen throughout the Great Depression and had not yet recovered, many lots sold for far less than they would have fetched during the late 1920s, when the sale of Jerome Kern’s book collection brought $1,729,462. (Although Kern died in 1945, he disposed of his book collection in January of 1929.) The three-volume catalogue of the famous Newton auction still serves as a reference for collectors of American and English literature.

FROM BUSINESS TO BOOKS

Born in Philadelphia in either 1863 or 1864 (depending on source), Newton was the son of Louise Swift Newton and Alfred Wharton Newton. He married Babette Edelheim in 1890, and they had two children, Caroline Newton and Edward Swift Newton. As president of a successful business in Philadelphia, the Cutter Electric Equipment Manufacturing Company, Newton was able to support his family, make frequent trips to London, and pursue his book-collecting passion. A book collector since childhood, Newton nurtured his ever-growing obsession with first editions, manuscripts, and book-related ephemera and eventually developed a renowned library at his home, “Oak Knoll,” outside Philadelphia in Daylesford, Pennsylvania. (Newton’s home, which has since been demolished, should not be confused with Oak Knoll Books and Oak Knoll Press in New Castle, Delaware.) In addition to collecting books from the 16th and 19th centuries, Newton helped foster an interest in English neoclassical writers (especially Samuel Johnson and James Boswell) during a period when their works were largely unappreciated. The main period of Newton’s book collecting and his writings on the subject coincided with America’s great boom in book collecting, which peaked between 1910 and 1930. The magnitude of his book purchases, the quantity and popularity of his books and magazine articles, and his “colorful public persona” (as at least one writer characterized his checkered suits and bow ties) guaranteed that he would play a central role in this boom.

NEWTON THE CLUBMAN

Like his good friend Christopher Morley, Newton was a “clubman.” He joined clubs, and he started clubs. Not surprisingly, he was a member of The Grolier Club, one of

America’s most respected and exclusive bibliophilic societies. In addition, he founded The Trollope Society in Philadelphia in 1929. (It preceded the American Trollope Society based in New York and the British Trollope Society based in London.) In founding the Trollope Society, he wrote: I am about to do a thing which may be very foolish: I am going to start a Trollope Society. I realise (sic) fully — no one better — that this is a bad time to start anything: nevertheless I shall try… I have something to suggest which will take our minds off our troubles…. A source of reading, the cheapest and most delightful pastime there is. And, in order that we may forget, I suggest a course of reading of the good old Victorian novels of Anthony Trollope. Here and now I proclaim the fact that Anthony Trollope has written a greater number of first class novels than Dickens or Thackeray or

George Eliot —I had almost said than these novelists combined —but I wish to be modest in my statements.

Not all of Newton’s club activities were book-related. According to J. B. Post, author of “A. Edward Newton and Oak Knoll,” Newton “was one of the founders of

the Tredyffrin Country Club, and was its first president until it was discovered he neither knew nor cared much about the game of golf.” In addition, Newton, along

with some of the other husbands in Daylesford, formed The Hen-Pecked Husbands Club (perhaps founded in the same tongue-in-cheek spirit as Christopher

Morley’s Three Hours for Lunch Club). Clearly, Newton was no bookish recluse but was, instead, a convivial participant in his community.

NEWTON’S LEGACY

In the 1930s, Newton started a competition to encourage and recognize book collecting among young people. Today the A. Edward Newton Student Book Collection

Competition is the nation’s longest-running collegiate book collecting contest. It awards cash prizes to three undergraduate Swarthmore College students who submit

the best essays and annotated bibliographies of their book collections (Each book collection must include at least 25 items and must have a thematic focus.) The winners are also invited to give a talk about their collections in Swarthmore’s McCabe Library. Since its founding, similar competitions have been established in more than three dozen colleges throughout the country.

Newton said, “Everyone’s shelf will

contain different books, and the books that give joy

to youth may not delight age, but the pleasure of

reading continues. The habit, firmly established,

enables one to endure, if need be, misfortune and even

disgrace.” It was this joy that fueled Newton’s passion for books, a passion he hoped to share with generations to come.

Read the rest of this issue here: PandB 2014 October

Comments are closed.